|

Discursive Polarization

Extreme forms of polarization can threaten the democratic social order. As scholars of media and communication, we focus on exploring the discursive dimension of polarization: how and why polarization emerges in mediated and interpersonal communication and what to do about this.

Discursive Polarization has been defined as polarization emerging and measured in communication. It can, analytically, be distinguished from cognitive polarization as measured, mostly, in surveys. Discursive polarization both reflects and impacts cognitive polarization. The two processes are thereby part of one and the same broad meta-process of social divergence.

Discursive polarization consists of different dimensions, and while past literature has not agreed on the labels and exact definitions of the different dimensions, a consensus seems to have evolved that at least two basic dimensions need to be distinguished: 1) Ideological polarization, denoting increasing disagreement about facts, values and ideas and 2) affective polarization in the form of increasing dislike towards out-groups. Polarization thus comprizes (a) rising disagreements between groups that (b) increasingly dislike the given outgroups. Untamed “pernicious” polarization ultimately hurts democracy, because society is split up into hostile camps that are unwilling and unable to negotiate or argue in civil ways and no longer respect mutual democratic rights and rules that apply to everyone.

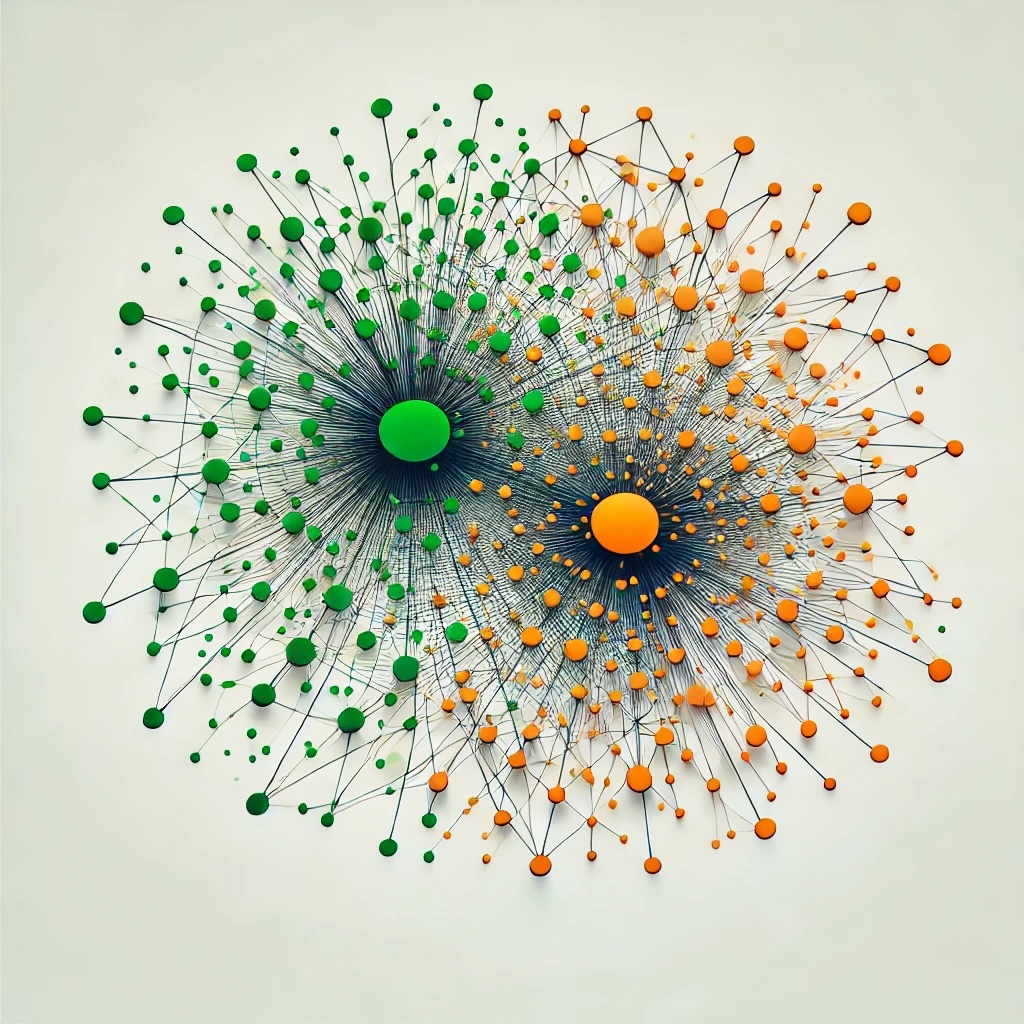

While the social sciences have explored polarization (particularly focussing on the United States), there is less research on its communicative dimension and its dynamics in other parts of the world, including Europe. The media, both news media and digital networks, are seen as drivers rather than as constraints on discursive polarization. News media foster polarization, e.g. by privileging extreme voices that provoke conflict and attention, thus contributing to provide a distorted perspective on public opinion and the different groups involved. For social media, this crowding out of moderate voices has been coined the “Social Media Prism”. Social media do not only offer space for extreme communities to form and polarize but also for “mutual group polarization” as only the worst from the outgroup is visible, as is the case in journalism. Both news and social media thus contribute to the imaginary of a polarized society - an idea that may serve as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Empirically, this process deserves further study as there are almost no studies that try to measure polarization in its different dimensions in news content, as a recent systematic review of the literature shows. Even less frequently studied is the polarizing process in direct interactions, and we therefore have limited understanding of how macro-level social processes of polarization manifest in micro-level interactions. Comparison of direct and mediated interactions could reveal the media contribution to polarization. Such analyses should, in contrast to most previous scholarship, disentangle the ideological and affective dimensions of polarization.

Brüggemann, M., & Meyer, H. (2023). When debates break apart: Discursive polarization as a multi-dimensional divergence emerging in and through communication. Communication Theory, 2–3, 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtad012