|

Narratives and Storytelling

Narratives play a large role in the way we make sense of our social environment and our place in it. Such narratives include both personal storytelling like the social chit chat of who does what with whom and the collective narratives of what is going on in the world. According to some studies, we spend 4-6 hours a day enmeshed in narrative thinking (Gottschall, 2012). The stories that we tell and that resonate with us are thus likely the basis of our attitudes, goals, and actions.

In narratives and stories, we (as audience) participate in the experiences of some main characters. The emotions and perspectives of these characters often become our emotions and perspectives. This effect of having a co-experience (Breithaupt, 2023) can be quite positive and lead to better understanding and empathy. However, it can also backfire and lead to polarization precisely because we share a perspective. In the case of conflict narratives and stories with different perspectives, the audience tends to take the one or the other perspective. Then, people tend to agree with their chose side–but at the costs of the other side. The other side can become demonized as evil or at least as less valid.

To observe this process of how narratives lead people to take a side and ignore others, I and my team have examined what we now call “spontaneous side-taking.” We ask to which degree does spontaneous side-taking “stick” and lead to polarization?

Our initial studies show that 1) people quickly choose a side when they are offered a conflict narrative, 2) that they stick to this side over time even when information is added that does not support their preferred side and 3) that they ignore the other, not-preferred choice.

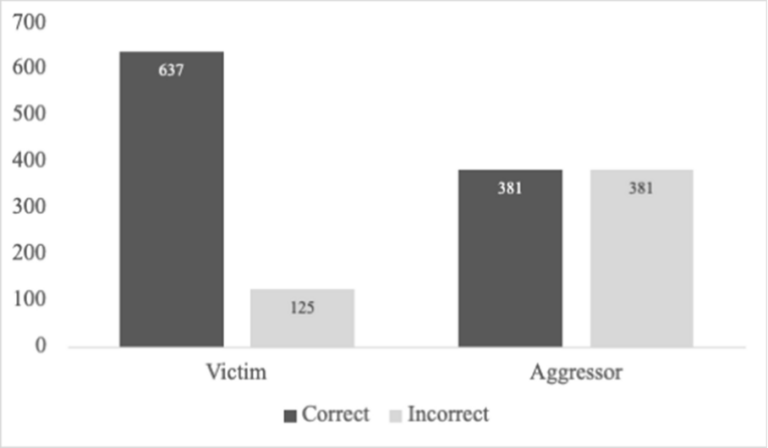

This figure shows how readers remember details about two characters in a story (such as clothes). In the balanced stories presented, both characters were aggressors and victims of half the actions. Nevertheless, most readers classified one character as victim and the other as aggressor, though it was undetermined upfront which was which. As a consequence of this preference choice, readers then remembered and likely paid much more attention to the “victim” but not the “aggressor.” This lopsided memory was a function of their preferred choice, and not the stories which were more balanced, see Woodward, Hiskes, & Breithaupt 2024.

The third aspect (see figure) was especially astonishing: people do not seem to pay much attention to others once they have made a choice. In our study, participants forgot many details connected to other sides but showed good memory of details (like clothes) of their preferred side. There are ongoing studies in this domain of work. It is likely that narratives contribute largely to how we attach ourselves to some groups and beliefs while dismissing or ignoring others. The next phase of our project is to test interventions that can undermine the negative effects side taking.

Woodward, C., Hiskes, B. & Breithaupt, F. Spontaneous side-taking drives memory, empathy, and author attribution in conflict narratives. Discov Psychol 4, 52 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00159-w